This is excerpted from Dr. Namika Sagara’s presentation at the 2016 National Medicare Supplement Sales Summit in Kansas City, MO.

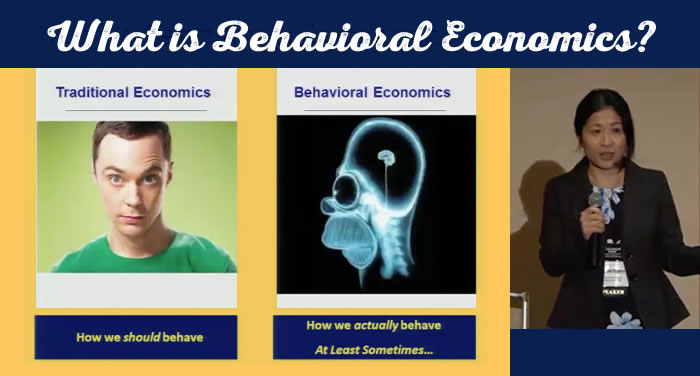

Traditional economists view people as rational decision-makers. We use the resources available to us to make the best and most informed decisions. We know what’s best for us, and make our decisions accordingly… or do we?

No, people aren’t always rational. If we were, we’d spend significant time deciding what to eat for breakfast, based on fiber and nutritional content, factoring in the previous day’s exercise or lack thereof. Instead, we make choices based on habits, instinct, and convenience. If we were rational we’d never have a problem with over-eating or under-exercising. We’d never have problems planning for the future and retirement, and we’d dutifully research and purchase the right types of insurance.

Research in behavioral economics shows that people often act against their own best interests, based on how questions are framed. Below are some fascinating experiments that show examples of this.

Framing: Polling Questions

In this experiment, participants were presented with the following scenario, asked in two different ways:

Imagine that the U.S. is preparing for an outbreak of a virus, which is expected to affect 600 people. There are two alternative programs.

Group 1 was presented with these options:

Program A: 200 people will be saved.

Program B: There is a ⅓ chance that everybody will be saved, and a ⅔ chance that nobody will be saved.

Group 2 was presented with these options:

Program A: 400 people will die.

Program B: There is a ⅓ chance that nobody will die, and a ⅔ chance that everybody will die.

How the groups answered

In Group 1, 72% chose Program A, and 28% chose Program B.

In Group 2, 22% chose Program A, and 78% chose Program B.

But the interesting thing is that if you look closely, you’ll see that both programs are identical. The only difference is in the wording. How we frame questions has a big impact on decision-making. People want to assure a gain or avoid a loss.

Framing: Life Expectancy

In this example, participants were asked a question about how long they expected to live, but the question was framed in 2 different ways.

Live-to framing:

The chances that I will live to be 85 or older is _____%.

Die-by framing:

The chances that I will die by 85 or younger is _____%.

For those that were asked using the “live-to” framing, the average answer was 55%. For those asked using the “die-by” framing, the average answer was 68% (or 32% chance to live to be 85+).

The researchers also found that the longer people expected to live, the more likely they were interested in an annuity, especially those asked using the “live-to” framing question.

Framing: Annuity Puzzle

Let’s say that we have a problem where not enough people are buying annuities. A traditional economist might say that a rational human being would understand the value of an annuity – not being able to outlive your income. If people aren’t buying annuities, we need to add more features/options, such as delayed annuitization, inflation protection, etc.

A behavioral economist would look at the problem differently. They might say that an aversion to annuities is not a fully rational phenomenon. It’s not what you are selling, it’s how you’re framing annuities.

Researchers performed an experiment where they told participants the following:

You will read stories about how Mr. Red and Mr. Gray are managing their retirement assets. They both:

- Are 65 yrs old

- Receive $1,000 month from Social Security

- Have already set aside money for their children

- Have $100,000 savings

After reading the stories about them, you will select the one whom you think made the better choice.

Investment Framing:

Mr. Red invests $100,000 in an account that earns $650 each month for as long as he lives. When he dies, the earnings will stop and his investment will be worth nothing.

Mr. Gray invests $100,000 in an account that earns a 4% interest rate. He can withdraw some or all of the invested money at any time. When he dies, he may leave any remaining money to his children.

In the example above, using investment terminology, Mr. Red represents an annuity, and Mr. Gray represents a savings account. Twenty-one percent of participants chose Mr. Red in this scenario.

Consumption Framing:

Mr. Red can spend $650 each month for as long as he lives, in addition to Social Security. When he dies there will be no more payments.

How long Mr. Gray’s money lasts depends on how much he spends. If he spends only $400 per month, he has money for as long as he lives. When he dies, he may leave the remainder to his children. If he spends $650 per month, he has money only until age 85.

In this scenario, using spending and payment terminology 72% chose Mr. Red’s annuity.

When framed as an investment, an annuity seems to be a risky investment, but when framed as something a client “gets” in the form of payments, an annuity seems like valuable insurance.

Loss Aversion: Coin Toss

Imagine you’ve been offered to play a coin toss game. If it’s heads you lose $1000. If it’s tails you win $____. How much would you potentially need to win to play this game?

Economists would say that if the amount is anything over $1000 you should play. But in reality, people perceive the loss of $1000 to be far more painful than they perceive the gain of $1000. This is “loss aversion”.

Framing: Deductibles

Imagine that you are looking for insurance for a $12,000 car you’ve just purchased. Suppose you are offered the policy below.

Deductible framing:

Annual Premium = $1000

Deductible = $600

Rebate framing:

Annual Premium = $1600

Rebate = $600 - a rebate of $600 minus any claims paid will be given to you at the end of the year.

People feel that a deductible is a loss, while they perceive a rebate as a gain. Option 2 is worse for the customer, but 68% of people were interested in that option.

Irrational valuation

In another example, two groups were asked about flight insurance. Suppose you are flying to London next week. You are offered a flight insurance policy that will provide $100,000 worth of life insurance in case of your death.

Group 1: Your policy covers death related to flying for any reason. How much would you be willing to pay?

Group 2: Your policy covers death related to any act of terrorism only. How much would you be willing to pay?

For Group 1 the average amount they were willing to pay was $12, and for Group 2 it was $14. People were willing to pay more for less coverage, based on their emotions. A combination of personal experiences, media coverage, and priming, results in vividness. This is why people are more afraid of flying than driving. When things are more vivid in our minds, we perceive a higher likelihood of it happening. This is irrational behavior.

Key takeaways

When communicating with clients, try to be mindful of framing.

- How are you communicating with regard to losses for clients (e.g. fees, time, inconvenience) and gains (e.g. short or long-term benefits)?

- Are your communications accidentally highlighting (potential) losses over gains?

Our decisions can be affected by seemingly irrelevant information without our awareness, so understanding how people actually make decisions can have a direct impact on your sales.